Synopsis

The document is about the author’s experience in India, where they traveled to explore consciousness and social construction. Specifically, they stayed in a roof top hut in Mahabalipuram and witnessed the receding waters before the 2004 tsunami hit. They also observed the aftermath of the disaster, including hunger and homelessness, and the efforts of NGOs to provide food aid.

What was the author’s purpose in traveling to India?

The purpose of the author’s travel to India was to gather data in a fresh environment, be inspired by the region, and document their travel experiences. They also aimed to synthesize their academic readings with decades of experiential research and explore questions related to consciousness and social construction.

How did the author describe their experience of witnessing the receding waters before the tsunami?

The author described witnessing the receding waters before the tsunami as an extraordinary event. They noticed that the waters had receded far from the coastline and there were no mud flats, which should have been evident. Instead of venturing forward to investigate like others, the author headed back to their roof to room.

What were the author’s observations of the efforts made by NGOs to provide food aid after the disaster?

The author observed that while official NGOs were only marginally active in providing food aid to villages along the coast, they took it upon themselves to buy food supplies from Chennai and deliver them to these villages. Initially, most villages were deserted and people seemed to be in a daze. However, the situation improved as more food drop-off points were set up by international NGOs, leading to a decrease in social upheaval and hunger along the coast.

Roof top hut saves the day.

Flight from the city

Embarking upon a journey to India, Mr. Italozazen sought not merely to traverse the physical landscape but to navigate the contours of meaning and the pathways to new enlightenment. Post-graduation, the metropolitan life of Australia’s bustling cities had been a crucible of academic endeavor and artistic exploration for Mr. Italozazen. Yet, the call to travel was an irresistible siren song, promising a synthesis of scholarly insights with the rich tapestry of lived experience.

The sojourn was not just a departure from the familiar shores but an odyssey towards a deeper understanding of the self within the cosmic play of consciousness. India, with its vibrant paradoxes and ancient wisdom, presented a canvas ripe for the experimental research that Mr. Italozazen had long pursued in the peripheries of Brisbane. It was in the embrace of India’s enigmatic aura that he aimed to document his journey, to capture the essence of his findings not just in words but through the very soul of his art.

In the coastal town of Mahabalipuram, as the year waned to a close in December 2004, Mr. Italozazen found exhilaration. Here, amidst the chisel of the sculptor and the chant of the priest, he encountered a milieu that was at once alien and intimately known. The artists he met, kindred spirits in their quest for innovation, offered new perspectives that challenged and expanded his own. Their visual art practices, a confluence of tradition and experimentation, mirrored his own quest to understand consciousness and the societal constructs that shape our perceptions.

Thus, the travel to India was not a mere change of geography; it was an intentional plunge into an environment that promised fresh data, inspiration, and a rekindling of the spirit. It was here that Mr. Italozazen’s decades of experiential research and recent academic rigor could coalesce, forging a new path in the pursuit of knowledge and artistic expression.

Tsunami pilgrim encounters the wave

In the wake of his relocation from the beachside to the elevated sanctuary of a rooftop hut, Mr. Italozazen, the Tsunami pilgrim, found himself unwittingly cast in a drama as ancient as the sea itself. The morning’s walk along the beach became a scene etched in memory, where the sea, in an act of mysterious retreat, had laid bare the ocean floor—a spectacle devoid of the expected mud flats, an anomaly in the rhythm of nature that whispered of impending change.

The artist, attuned to the nuances of his environment, sensed the surreal nature of the unfolding scene. His decision to retreat was not driven by fear but by an intuitive understanding that the earth was scripting a narrative of its own. As he ascended to his rooftop refuge, the air was suddenly rent with cries of “TANI TANI!”—a primal alarm that surged through the narrow paths of Mahabalipuram.

The first wave, as if to confirm the fears of the locals, had indeed made its claim upon the land, reaching just to the precipice of Mr. Italozazen’s newfound abode. The water, a force both creative and destructive, had in one breath sculpted a new landscape of urgency and survival.

With the artist’s spirit composed yet vigilant, he emerged to witness the aftermath—a tableau of the water’s embrace, lapping at the foundations of buildings far from its natural berth. Here, 300 meters inland, the sea had dared to venture, leaving the indelible mark of its passage.

This encounter with the wave was not merely a brush with nature’s might but a profound moment of communion with the forces that shape our existence. For Mr. Italozazen, it was a testament to the power of observation and the wisdom of restraint. The experience would later animate his art, infusing it with the raw energy and transformative essence of the wave—a syncretic blend of his journey, his research, and the indomitable spirit of the places that had imprinted themselves upon his soul.

Hunger and homelessness pervade the coast.

In the shadow of the great wave’s retreat, a stark tableau of human need unfurled along the coast. The once tranquil temple grounds became a crucible of survival as hordes of villagers, their faces etched with the raw urgency of hunger, gathered in a desperate congregation. The air was thick with the dust of chaos as trucks laden with sustenance arrived, their cargo of bread tossed into the outstretched hands of the famished. Yet, in this scramble for life’s basic nourishment, the bread was often snatched from grasp to grasp—a stark testament to the primal instinct to survive that Mr. Italozazen had never before witnessed on such a scale.

As days passed, the tumultuous waves of social upheaval began to ebb, quelled by the steady influx of aid from international non-governmental organizations. Food drop-off points emerged like beacons of hope amidst the encampments, signaling a semblance of order rising from the depths of despair.

Amidst this landscape of recovery, Mr. Italozazen, the Tsunami pilgrim, found solidarity with fellow travelers. Together, they ventured beyond the reach of official aid, carrying sustenance from Chennai to the scattered villages along the coast. Their journey was a pilgrimage of compassion, delivering not just food but a message of shared humanity to those who remained, dazed yet enduring, amidst the ruins of their former lives.

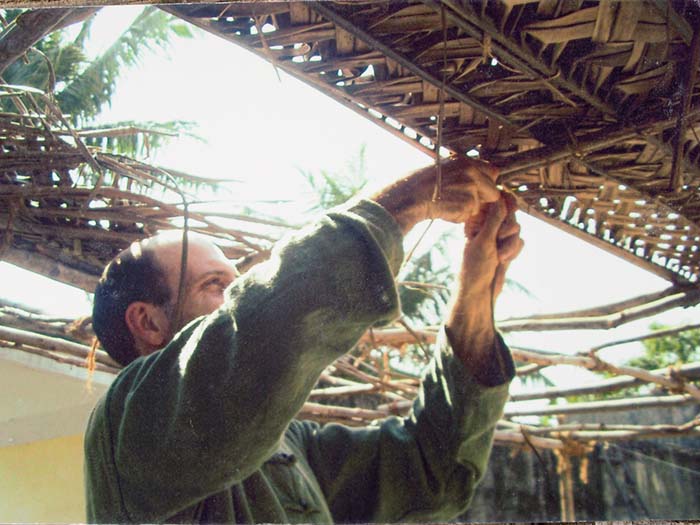

Choosing to immerse himself in the fabric of Mahabalipuram, Mr. Italozazen embraced the art of sculpture, joining the granite stone carvers in a dance of creation and restoration. It was a communion of spirit and stone, a gesture of rebuilding that transcended the physical to touch the very soul of culture.

The invitation to join the annual pilgrimage to Iyaypan came as a natural progression in his journey. With the guild of carvers, a cohort from Mamallapuram district, he set forth on a ten-day odyssey, a sacred march intertwined with the footsteps of many other pilgrims. This was not merely a journey across land but a passage through the heart of resilience, a testament to the enduring spirit of a community in the face of nature’s unfathomable power.