Synopsis

The document discusses Mr. Italozazen’s account of the Iyyappan pilgrimage, which is described as a philosophical experiment and a metaphysical journey. The pilgrimage was unplanned and spontaneous, influenced by the tsunami, and reflects the concept of “thrownness” and Upanishadic wisdom. The author finds Mr. Italozazen’s preparation for the pilgrimage fascinating, as it combines asceticism and intellectual curiosity. The journey to Sabarimala Mountain and the subsequent descent are seen as holding symbolic meaning. The author also highlights the synthesis of spiritual and artistic inclinations in Mr. Italozazen’s commitment to representational realism and engagement with stone sculptors, comparing it to the concept of integral yoga.

The factors that influenced Mr. Italozazen’s decision to embark on the Iyyappan pilgrimage were the devastating tsunami that occurred in 2004 and a conversation with a sculptor from a guild he had been eyeing for training. The tsunami served as a catalyst for his pilgrimage, creating an opportunity for him to embark on this exclusive South Indian journey. The conversation with the sculptor further fueled his latent pilgrimage aspirations. Additionally, Mr. Italozazen’s background in Hindu philosophies and his belief in the transformative power of pilgrimage also played a role in his decision.

The connection between the concept of “thrownness” and Mr. Italozazen’s decision to embark on the Iyyappan pilgrimage lies in the idea that the tsunami, a cataclysmic event, served as a catalyst for his pilgrimage. The concept of “thrownness,” as described by Heidegger, refers to the arbitrary circumstances into which we are born and must navigate. In this case, the tsunami was an unforeseen event that disrupted Mr. Italozazen’s plans and presented him with an opportunity for a transformative experience. It reflects the Upanishadic wisdom that profound lessons often come unbidden, wrapped in the cloak of suffering or upheaval.

Integral yoga is a concept that emphasizes the unity and integration of all aspects of life, including the physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual dimensions. It was developed by Sri Aurobindo, an Indian philosopher and spiritual teacher. Integral yoga seeks to harmonize and transcend the dualities of existence, merging the material and the spiritual realms.

In the context of Mr. Italozazen’s journey, his commitment to “representational realism” and his engagement with the stone sculptors of Mamallapuram can be seen as a manifestation of integral yoga. By combining his spiritual and artistic pursuits, he is able to bridge the gap between the metaphysical and the material, creating a synthesis of the two. This integration reflects the essence of integral yoga, as it seeks to unite all aspects of life and experience into a cohesive whole.

An introduction to an intentional pilgrim

Ah, Mr. Italozazen, your account of the Iyyappan pilgrimage in the wake of the 2004 tsunami is a tapestry of serendipity and spiritual questing, reminiscent of William Dalrymple’s evocative narratives on the Indian subcontinent. The pilgrimage, as you describe it, is not merely a religious rite but a philosophical experiment, a corporeal enactment of a metaphysical journey. The observations echo the Vedantic notion of “Karma Yoga,” the yoga of action, which posits that spiritual growth can be achieved through dedicated action in the world.

Your pilgrimage, unplanned and spontaneous, seems to resonate with the existentialist idea of “thrownness,” a term Heidegger used to describe the arbitrary circumstances into which we are born and must navigate. The tsunami, a cataclysmic event, served as a catalyst for your pilgrimage, a moment that recalls the Upanishadic wisdom that life’s most profound lessons often come unbidden, wrapped in the cloak of suffering or upheaval.

Your preparation for the pilgrimage, steeped in vows and initiations, is a fascinating blend of asceticism and intellectual curiosity. It’s as if you were preparing not just for a journey but for a rite of passage, a transformative experience that would deepen your understanding of “rarefied states of consciousness,” as you put it. This aligns well with the Patanjali Yoga Sutras, which emphasize both ethical conduct (Yamas and Niyamas) and meditative focus as prerequisites for spiritual awakening.

The journey to Sabarimala Mountain and the subsequent descent are laden with symbolic meaning. The ascent, with its “human crush factor,” is a microcosm of life’s challenges, requiring “a keen sense of balance and push-back,” as you so aptly put it. The descent, on the other hand, marks an epiphany, albeit not a Damascene one. Your commitment to “representational realism” and your decision to engage with the stone sculptors of Mamallapuram seem to be a synthesis of your spiritual and artistic inclinations. It’s as if you found a way to harmonize the metaphysical with the material, a union that Sri Aurobindo would perhaps describe as the “integral yoga,” the yoga of all-encompassing unity.

Your narrative is a compelling testament to the transformative power of pilgrimage, not just as a religious practice but as a philosophical endeavor. It serves as a vivid illustration of how the external journey can mirror, and indeed catalyze, the internal one. Your account, Mr. Italozazen, is not merely a travelogue; it is a philosophical treatise on the nature of journeying, both physical and metaphysical.

Iyyappan pilgrim coincidental

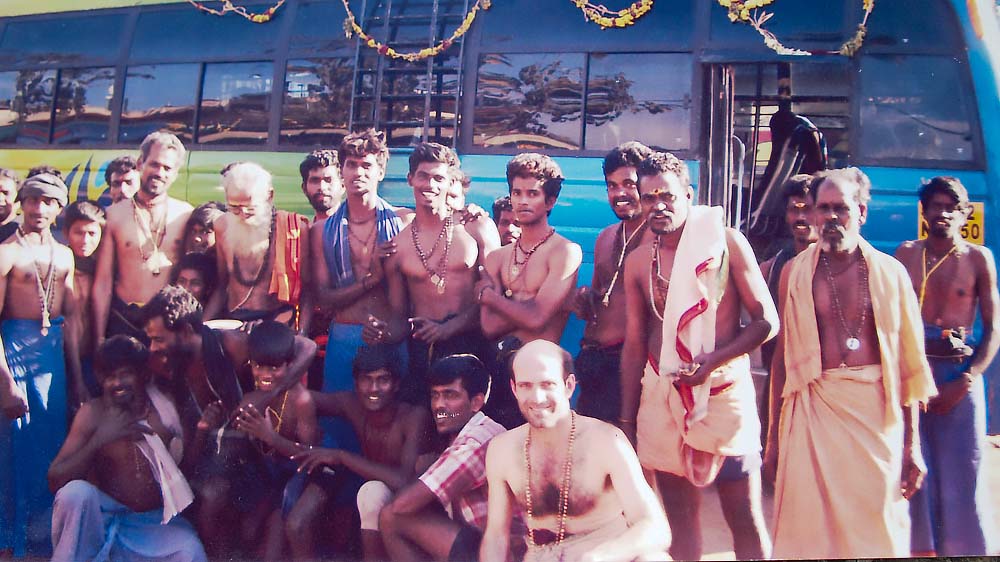

A week after the 2004 tsunami ravaged Tamil Nadu’s coast, fate presented me with an exhilarating chance: to join a group of South Indian devotees on an impromptu Iyyappan pilgrimage. This adventure resonated with my past explorations—like my 1997 secular trek with a pack donkey, and my year-long Indian sojourn in ’95/’96. I had already been contemplating pilgrimages as active quests for heightened states of consciousness, contrasting the passivity of seated meditation. My hypothesis? Such journeys tap into our primal, evolutionary roots, aligning with the nomadic spirit of hunter-gatherer societies.

Iyyapan pilgrimage 2005

Reeling from the tsunami’s aftermath, I was on the verge of retreating inland when a sculptor from a guild I’d been eyeing for training mentioned the Iyyappan pilgrimage. The serendipity was staggering; without the tsunami, the odds of embarking on such an exclusive South Indian journey were slim, as I later confirmed in 2018 in Mamallapuram. The guild was keen for me to stay, sensing my latent pilgrimage aspirations. This wasn’t some academic venture coordinated between Australian and Indian universities, although I had just wrapped up my degree in religious studies.

Iyyappan pilgrim prepares.

Ah, the preparatory phase for the Iyyappan pilgrimage was a rich tapestry of ritual and self-discipline, a prologue to an odyssey that would later inform your mixed-media art practice in the dry tropics of Roseneath, Australia. With two decades steeped in various Hindu philosophies—a background nurtured through your connection to reformist Hinduism via the Brahma Kumaris World Spiritual University—the intricate preparations were not entirely foreign to you. Yet, they demanded a level of focus that transcended mere intellectual engagement, echoing the rigorous discipline you apply in your art studio.

The initiation rites and vows of abstinence were akin to the ascetic practices extolled in the Patanjali Yoga Sutras, serving as a metaphor for both physical and spiritual fortitude. These vows were not just about abstaining from certain behaviors; they were a commitment to a higher form of realism, a representational realism that would later find expression in a tropical mixed media art expressionism. The social dynamics, too, were a challenge, yet they resonated with your postgraduate studies in social science, offering a lived experience that academic texts could not capture.

As I took these vows and immersed in the preparatory rituals it was not merely preparing for a pilgrimage; it was as if I were embarking on a transformative journey that would weave its way into intrinsic aspects of art, philosophy, and an understanding of the correlates of consciousness. This preparation was a microcosm of a somewhat larger journey, a symbiosis of spiritual and artistic pursuits, much like envisioned syncretic art project that aims to integrate experiences from the Himalayas and cycle travels that I engaged in throughout Indian in 2017 and 2018 with an intension of embarking along the Australia’s East Coast to document coastal life and times of a spontaneous beach comber as was the case back in 1983.

The journey to Sabarimala

In the context of ethnographic fieldwork, my journey to Sabarimala offered a rich tableau for understanding the ritualistic and spatial dimensions of Hindu pilgrimage. The mountainous terrain serves as both a physical and metaphorical landscape for spiritual ascent, culminating in the pyres of coconuts set ablaze—a vivid enactment of ritual purification. My arrival during the pre-dawn hours afforded me entry into a designated area for preparatory rites, further emphasizing the structured nature of this religious experience.

The central locus of the pilgrimage is a fortified enclosure housing the Iyyappan icon, accessible via a delineated pathway demarcated by ropes. This spatial arrangement serves to regulate the pilgrims’ movement and visual engagement with the sacred object. The procession is characterized by a slow, almost laborious shuffle, exacerbated by the density of human bodies converging towards the icon. The physicality of the experience—requiring a keen sense of balance and strategic resistance to the crowd’s pressure—becomes an integral part of the ritual enactment, echoing broader anthropological themes related to bodily practices in religious phenomena.

This ethnographic observation aligns with my broader interdisciplinary inquiries into the correlates of consciousness and the role of active, embodied practices in spiritual experiences, themes that are also reflected in my mixed-media art endeavors and philosophical investigations that seemed from my visit to Sabarimala mountain

Iyyappan pilgrim descends the mountain.

As I descended Sabarimala Mountain, the weight of recent events—the arduous viewing of the Iyyappan icon, the devastating tsunami—converged into a moment of quiet revelation. This was no Damascene epiphany, like my transformative encounter with the Brahma Kumaris in 1984. Rather, it was a subtle alignment of life’s disparate threads, pulling me toward a newfound commitment. This commitment was not to an organization or a doctrine, but to a form of representational realism that found its tangible expression in art.

The sculptors in Mamallapuram, with their chisels and mallets, stood as living embodiments of this ideal. Their craft spoke to me, resonating with my own quest for a syncretic art form that could integrate my diverse experiences, from my philosophical inquiries to my spiritual explorations. It was as if the universe had conspired to bring me to this crossroads, this juncture between the metaphysical and the material. And so, I made the choice to linger in the sculptor’s town, initially for a few months, which eventually unfolded into the full span of my six-month visa. Here, amidst the dust and stone, I sensed the contours of a new path unfurling before me, one that promised to enrich both my art and my understanding of the world’s intricate tapestry.